Aluminum demand is predicted to continue growing strongly into the foreseeable future—consequently, the world needs more bauxite. With the market now in deficit, E&MJ looks at trade trends and potential projects.

By Simon Walker, European Editor

| |

| A bauxite stockpile at Wagerup in Western Australia, one of four alumina refineries in the state. (Photo courtesy of Alcoa) |

In January 2014, the Indonesian government put a cat amongst the pigeons with the introduction of its ban on exports of unprocessed raw materials. And while public attention focused mainly on the country’s copper producers—with Freeport subsequently being able to resume concentrate exports while committing to the development of new domestic smelting capacity—the ban also had a substantial impact on other mineral products, including bauxite and nickel laterite ore.

To place things into context, Indonesia was the world’s fourth-largest bauxite producer in 2012, accounting for 12% of global output. Virtually all of that was exported unprocessed, with China the principal destination.

An article published in May 2014 in The Financial Times(FT) reported on the impact that the ban was then having on one bauxite-producing company with its operations in west Kalimantan. The Harita group began bauxite production in 2005, and by 2013 was exporting 12 million metric tons per year (mt/y). Much of that was delivered to the Chinese aluminum producer, China Hongqiao, which is providing financing for a new alumina refinery now under construction nearby. Scheduled to come on stream in 2016, the plant will convert some 7 million mt of bauxite into 2 million mt/y of alumina, although, as the FT article pointed out, this will still leave Harita with 5 million mt/y of bauxite capacity that will either be lost or will be subject to escalating taxes if the company decides to maintain its export levels.

And while the country’s mineral producers are unhappy about having to fund new refining capacity in what many perceive is an already oversupplied market, Harita is not the only one to have committed to construction. In fact, the Indonesian government now predicts that no fewer than five new alumina refineries will be built before 2020. With Rusal having indicated that it intends to use Indonesia as its regional alumina hub—involving $2 billion in capex for a 1.8-million-mt/y-capacity refinery—another Russian company, Vi Holding, reported to be investing some $500 million in a new plant in the country. Rusal was due to complete a feasibility study on its project by the end of last year, having shelved previous proposals made in 2007.

In the meantime, the Chinese aluminum industry has had to look elsewhere for its bauxite supplies, with spot prices during the first half of 2014 jumping from near $50/mt early in the year to as high as $95/mt as buyers looked to replace material previously supplied from Indonesia. One country in particular to benefit has been Malaysia, where exports to China reportedly rose 20-fold last year to 3.3 million mt and further substantial increases are anticipated. Other countries that have also increased their stake in the China trade include Australia, India, Ghana, Guinea and the Dominican Republic, although from a transport perspective, Malaysia and Australia hold stronger cards than some of the other contenders.

However, the companies exploiting the new-found market for Malaysian bauxite—and the mines that are being developed to meet it—may have to come to terms with the realities of shipping this type of bulk cargo. On January 2, the bulk carrier Bulk Jupiter, carrying 46,400 mt of bauxite from the eastern Malaysian port of Kuantan to China, capsized and sank off Vietnam, with the most probable cause being the liquefaction of a cargo that had been loaded with too high a moisture content after recent heavy rain. Unfortunately, this was far from being an isolated incident, with several bulkers, carrying bauxite or nickel laterite ore, having sunk in similar circumstances over the past few years while plying between southeast Asian countries and China.

PRODUCTION GROWS, PRICING CHANGES

PRODUCTION GROWS, PRICING CHANGES

Over the past 15 years, the world’s output of both bauxite and alumina has more or less doubled. According to data complied by the British Geological Survey (BGS), USGSand International Aluminium Institute and shown in the graph above, in 1999, the world produced 129 million mt of bauxite from which 50.2 million mt of alumina were refined. For 2014, the totals were estimated at 234 million mt and 108.4 million mt, respectively, but while the output of alumina rose slightly from 2013, bauxite production fell by more than 50 million mt as a direct result of the Indonesian export ban.

One interesting fact to emerge from these data is that the yield of alumina from raw bauxite has remained virtually unchanged at a little more than 38% over this period, suggesting that, on average, the grade of bauxite resources being mined has also been maintained. Unlike some other commodities, the bauxite industry does not yet appear to be faced with a declining long-term grade profile.

Aluminum production, and the bauxite and alumina that make up the process chain, is essentially a 20th century industry. Again, according to the BGS, in 1915, the entire world produced somewhat more than 500,000 mt of bauxite, with France and the USA accounting for more than 97% of this between them.

By 1962, world bauxite production had risen to 31 million mt (see table at right), with Jamaica, the USSR and Suriname the top producers. Fifty years on, and these three (with Russia and Kazakhstan having replaced the USSR in this respect) remain in the world top 10, but their leading positions have been usurped by Australia, China and Brazil. Australia’s first bauxite mine, at Jarrahdale in Western Australia, came on stream in 1963, since when the industry has been on a continuous growth track.

By 1962, world bauxite production had risen to 31 million mt (see table at right), with Jamaica, the USSR and Suriname the top producers. Fifty years on, and these three (with Russia and Kazakhstan having replaced the USSR in this respect) remain in the world top 10, but their leading positions have been usurped by Australia, China and Brazil. Australia’s first bauxite mine, at Jarrahdale in Western Australia, came on stream in 1963, since when the industry has been on a continuous growth track.

The development of alumina-refining capacity has run hand-in-hand with rising bauxite production, although not necessarily in the same localities. Existing infrastructure has been a key factor in this respect with, for example, Jamaica’s bauxite initially being refined in the USA and elsewhere until domestic capacity came on stream. Guinean bauxite production is in the same position today, with only limited internal alumina refining supplemented by raw bauxite exports, while as has been noted above, the Indonesian government is set on adding value to its resources as a means of generating greater income from them.

Another major change that has occurred within the alumina business has been the move away from aluminum-related pricing and the introduction of contracts tied to price indices. Alcoa and BHP Billiton led the way in 2010, arguing that the traditional pricing system for long-term contracts, which valued alumina at around 12%-14% of the aluminum price, did not really reflect production and transport costs and effectively undervalued alumina.

In part, the move was also triggered by a change in the dynamics of aluminum production. Vertical integration within the industry, with individual companies controlling all stages from mining to ingot, is less of a feature now than it was in the past, while a new group of smelters has emerged that are dependent on securing their alumina supplies on the spot market.

Alcoa CEO Klaus Kleinfeld noted at the time that “an alumina index price gives more flexibility and reflects alumina’s short-term volatility. I think the customer understands why a change like that is needed, because alumina has very different cost drivers from aluminum,” he was reported as saying.

E&MJ asked Julio Moreno, senior analyst for raw materials intelligence at Harbor, to explain how the new pricing system had impacted the alumina market. “Index pricing has largely reflected market fundamentals,” he said, “which has been important since some consumers were afraid that this would not be the case.

“Over the past five years, the index price has ranged from a low of around $300 to a high of $420, while the price differential to aluminum metal has now risen to around 18%,” he said. “And producers are getting more of their sales using this system.”

In February of this year, alumina was trading at around $340/mt, although a few months earlier Chinese smelters were reported to be paying up to $370/mt in order to secure supplies and build up stocks before winter set in. Indeed, in November, Goldman Sachs predicted that the price will have to rise to $380 in the second half of 2015 in order to spur new production, while predicting that a market deficit of some 138,000 mt in 2014 will widen to more than 600,000 mt this year.

“There is an unprecedented idiosyncratic factor impacting the alumina market at present—Indonesia’s bauxite export ban,” the company said. “This has driven the bauxite market into an ongoing deficit, and has contributed to the slowdown in alumina output growth in China.”

In addition, it is estimated that bauxite stockpiles built up by Chinese refineries and smelters before the ban took effect have been depleting at a rate of 1 million mt/month, with the country facing a 10-15-million-mt bauxite shortfall unless alternative supplies can be sourced. Moreno pointed out that the country’s refineries use some 45 million mt/y of imported bauxite, with estimates indicating that China currently holds enough stocks for another year.

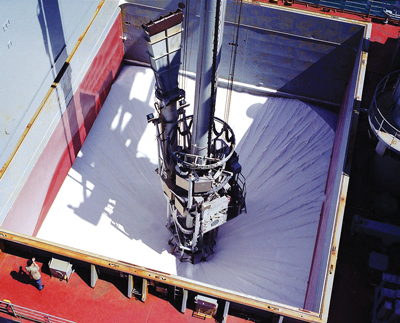

| |

| Unloading a cargo of alumina, with ship-borne trade having grown steadily. (Photo courtesy of Alcoa) |

AUSTRALIA’S PROJECT PIPELINE

Australia currently has five bauxite mines in operation, feeding six alumina refineries. Rio Tinto Alcan’s Gove and Weipa mines are in the Northern Territory (NT) and Queensland, respectively, while Alcoa operates Huntly and Willowdale in Western Australia (WA)—also home to BHP Billiton’s Boddington mine. The world’s largest bauxite mine, Huntly, alone has an output of some 23 million mt.

| |

| A bauxite stacker at Huntly in Western Australia, the world’s largest individual producer. (Photo courtesy of Alcoa) |

In terms of refineries, Alcoa operates its Pinjarra, Kwinana and Wagerup refineries through AWAC, its joint venture with Alumina Ltd., while BHPB’s Worsley plant refines alumina from Boddington bauxite. Rio Tinto Alcan’s refinery interests encompass the Yarwun plant at Gladstone, and its 80% stake in the nearby Queensland Alumina refinery in partnership with Rusal. Alumina production at its Gove refinery was run down during 2014, with the plant now on care-and-maintenance.

The continuing rise in demand has, not surprisingly, underpinned widespread interest in opening new resource areas in both the existing mining districts of Queensland and WA, but also as far afield as Tasmania. However, there are significant differences in terms of bauxite quality, with those in Queensland and the NT grading between 49% and 53% Al2O3 while the WA deposits are low-grade in international terms, at 27%-30% Al2O3. The compensation here is that the WA bauxites have low reactive silica contents, simplifying refining.

Probably the longest-running bauxite project never to have got off the ground, Aurukun is now being evaluated by Glencore, which somewhat controversially won the Queensland government’s latest selection process for the deposit last August. Located not far from Weipa on the state’s Gulf of Carpenteria, Aurukun was first held by Billiton and Pechiney; Chalco won a renewed bid in 2007 but later withdrew when it was unable to meet specific development terms; and the government had a five-strong shortlist of potential developers in 2013.

In the end, Glencore has been declared the “preferred proponent” for the project, although the company acknowledged that it will take up to four years to complete its studies and negotiate an indigenous land-use agreement. Resource estimates for Aurukun exceed 300 million mt.

Other projects currently under evaluation in northern Queensland include Cape Alumina’s Pisolite Hills and Bauxite Hills deposits, with resources of 135 and 60 million mt of bauxite, respectively. In December, Gulf Alumina issued a resource estimate of 63 million mt of direct-shipping ore for its Skardon River project, further up the coast, with work under way to convert this to JORC-compliant status. And, of course, Rio Tinto Alcan is working on a feasibility study for its South of Embley project, for which it gained government environmental approval in 2013. Located 45 km from Weipa, South of Embley could produce up to 50 million mt/y of bauxite products, and extend the life of the Weipa operations by around 40 years, the company said.

In Tasmania, Australian Bauxite has begun construction at its Bald Hills deposit, the first of three mines that it plans to open by 2018 that will have a combined output of 2 million mt/y. The company noted that Bald Hills will be the first new bauxite mine to open in Australia in 35 years.

WEST AFRICA: MASSIVE RESOURCES

Although production has been limited by infrastructure and foreign investment constraints, several West African countries host potentially economic bauxite resources. Of these, Guinea is the only country where production has been achieved in any meaningful manner; with an estimated 7,400 million mt in resources, that is perhaps unsurprising.

In Sierra Leone, Vimetco subsidiary Sierra Minerals produces around 1.2 million mt/y of bauxite that feeds the company’s own alumina refinery in Romania. In Nigeria, ALSCON produced its own bauxite feed for its smelter until 1999, when mining ceased, while Ghanaian production is now controlled by the Chinese company, Bosai Minerals Group. Bosai bought Rio Tinto Alcan’s 80% stake in Ghana Bauxite in 2010.

Compagnie des bauxites de Guinée (CBG) is not only Guinea’s largest company but, from its Sangaredi mine, is the world’s largest bauxite exporter. The company, in which Rio Tinto Alcan and Alcoa are the largest industry shareholders, produced a record 15.8 million mt of bauxite last year. The other main producer in Guinea, Rusal, reported 3.3 million mt of bauxite from its Kindia mine, but no bauxite or alumina from Friguia, where it has been in dispute with the government over ownership since 2009. In July last year, the company won an arbitration ruling on this—and another later in the year over its ownership of ALSCON in Nigeria. Both cases revolved around whether Rusal had paid a fair price when taking over the facilities.

In northwest Guinea, Alliance Mining Commodities (AMC) received confirmation of its mining convention over the Koumbia bauxite deposit in October, with a feasibility study in 2012 having estimated capex at $812 million to build an operation capable of producing 10 million mt/y of direct shipping ore over a 40-year life. Initial production is now expected next year, with nameplate capacity achieved in 2019.

Access to port facilities is, of course, a challenge, with AMC considering two options: either linking in to the existing railway that runs from CBG’s Boké mines to Kamsar on the coast, or construction of its own 125-km-long line to a new port on the Rio Nuñez, with subsequent barge shipment downriver to offshore loading facilities.

With its headquarters in Ireland, Anglo-African Minerals is also evaluating bauxite resources in Guinea, with four deposits in its focus. In January, the company presented an initial inferred resource estimate for one of them, Toubal, at 722 million mt grading 42.6% Al2O3, together with the results of a scoping study on the smaller FAR prospect.

Meanwhile, early last year, the Guinean government sought interest in three large blocks that were evaluated by BHP Billiton between 2006 and 2011. Shandong Xinfa Aluminum & Electricity Group was later reported to be negotiating over them, but seems to have been sidelined after the government selected the Huafei Group as its preferred bidder for Boffa Nord, Boffa Sud and Santou-Huda—with $700 million required in earnest money and a $1 billion investment commitment.

Also in line for big spending will be new railway links between Bamako in Mali and the ports of Dakar in Senegal and Conakry in Guinea. The Malian government has contracted with China Railway Engineering Corp. to upgrade the existing line to Dakar and prepare a feasibility study on the all-new Conakry line, with the aim of improving transport for potential iron ore and bauxite mining in the country. Capex of $1.5 billion and $8 billion has been quoted for the two parts of the project.

CHINA: THE GREAT CONSUMER

By all accounts, China’s position in the bauxite-producers league table belies its endowment, which is limited and of rapidly declining grade and quality. Large-scale mining only dates back to the 1980s, with domestic production growth having been driven by demand from the automotive and construction industries. Production is largely centered on the provinces of Henan, Guizhou, Guangxi and Shanxi.

Although Henan holds the largest proportion of reserves, the three largest bauxite producers—Jiakou (6.4 million mt/y capacity), Xiaoyi-Xingan (6 million mt/y) and Xiaoyi-Shaoy (5.9 million mt/y) are all situated in Shanxi. Much of the recent investment in the country has been directed toward new alumina-refining capacity, frequently reliant on imported bauxite.

Chalco, the operating subsidiary of Chinalco, produced 16.3 million mt of bauxite from its domestic mines during 2013, and is constructing an additional 1.6 million mt/y of capacity at its new Duancun-Leigou mine, with commissioning scheduled for December. It also has development projects in Indonesia and Laos.

Chinese alumina refiners began stockpiling bauxite well before Indonesia’s export ban came into force, and these stocks are now beginning to run down. In May 2014, commercial intelligence company Wood Mackenzie forecast that the country will need to tap massive new resources if its future plans for aluminum production are to be realized.

Wood Mackenzie’s head of metals and mining research, Julian Kettle, said, “China is the main global player in the aluminum market representing 40% of supply and 60% of demand. Our most recent forecasts indicate

that global alumina refinery production will rise to almost 140 million mt by 2018, which means we’ll see bauxite demand rise by almost 80 million mt to 350 million mt.

“With China’s alumina demand set to increase so sharply, there will be huge implications for bauxite demand,” Kettle said. “We estimate that China will need access to as much as 240 million mt of bauxite by 2030, and as it only produced 72 million mt domestically in 2013, huge uncertainty remains over the import versus domestic supply mix.”

The company suggested that three major resource areas in Guinea, Australia and Vietnam could more than enough meet China’s needs, although there are significant challenges to be overcome. Analyst Carl Firman questioned whether China would be prepared to “put all of its eggs in three baskets,” since its history of diversifying supply would suggest otherwise. And there is another potential source of alumina, Wood Mackenzie pointed out: fly ash from coal-fired power stations. “By investing in the development of new technology to extract alumina from fly ash, China could significantly reduce its bauxite requirement,” Kettle said.

AROUND THE WORLD

In its most recent business update, Alcoa noted that its 1.8-million-mt/y joint venture refinery with Ma’aden in Saudi Arabia is now fully operational, having produced its first alumina from local bauxite during the fourth quarter of 2014. The Al Ba’itha mine was also commissioned during the year at an initial capacity of 4 million mt/y of bauxite that is shipped by rail to the refinery and smelter complex at Ras Al Khair. Total capex for the project, which has been under development since 2009, has been some $10.8 billion.

| |

| Filters at the Friguia alumina refinery in Guinea; the 618,000-mt/y plant is currently shut. (Photo courtesy of UC Rusal) |

In Guinea, Alcoa and Rio Tinto Alcan are continuing with an evaluation of their long-delayed 1.5-million-mt/y refinery, while in Western Australia Alcoa’s plans to expand capacity at the Wagerup refinery to 4.7 million mt/y remain on hold—as does its proposed joint venture in Vietnam with Vinacom over the Gia Nghia mine-refinery project.

In December, Rusal completed the purchase of the 20% of OJSC Boksit Timana that it did not already own. The company said at the time that this move was part of its asset consolidation program, aimed at securing raw material supplies for its plants. The head of Rusal’s alumina division, Yakov Itskov, noted that the Timan deposits host 30% of Russia’s bauxite reserves, are of high quality and can be surface-mined. In particular, the Vezhayu-Vorykvin deposit has a reserve estimated at 260 million mt, with an annual output of 3 million mt being used for alumina production at Rusal’s Urals and Bogoslovsk refineries.

Meanwhile in India, Vedanta Resources has indicated that it is ready to expand capacity at its under-utilized Lanjigarh refinery from the current 1 million mt/y up to as much as 6 million mt, subject to bauxite becoming available. With its original plans for sourcing ore from the Niyamgiri Hills deposits scuppered following a referendum within local communities, Vedanta has had to resort to importing bauxite from other Indian states and from abroad to keep the plant running.

BAUXITE TO REMAIN IN DEFICIT?

According to Harbor’s aluminum intelligence unit, the world bauxite market registered a production shortfall of 2.6 million mt last year, with the likelihood of deficits averaging 11.5 million mt/y up to 2019. Citigroup put the 2014 deficit even higher, at around 6.3 million mt. For alumina, the picture is different, however, with Harbor estimating a market surplus of around 1 million mt for 2014 and what the company describes as “a well-supplied market” this year.

Harbor also noted in recent editions of its Alumina and Bauxite Intelligence Report that planned new alumina refining capacity may be delayed because of a shortage of feed or funding. In particular, it identified two projects in Brazil with a total capacity of more than 4.8 million mt/y that are in this position, together with 3.5 million mt/y in India. “At least one of these projects would be needed during this period to avoid a global production shortfall in 2017-2019,” the company added.

According to International Aluminium Institute data, world production of alumina totaled 108.4 million mt last year, comprising an estimated 51.3 million mt (47.1 million mt reported and 4.2 million mt unreported) in China, and 57.1 million mt for the rest of the world. This compared with capacity of 65.5 million mt for the rest of the world, and undetermined capacity in China—indicating that the industry, excluding China, was running at about 87% capacity utilization.

Moreno noted that although a portion of the currently idled capacity is at the high end of the cost curve, recent falls in energy prices will have restored some plants to competitiveness. “The situation has changed over the past couple of months, and there is a chance that some plants that were idle because of the cost of fuel oil may be brought back into production now oil is cheaper,” he said.

Moreno also commented on where new bauxite mines and alumina refineries may be located. “Mines will mainly be greenfield,” he said, “with countries with well-developed infrastructure—and closer to China—at an advantage, including Australia, Malaysia, other southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam and Laos; Fiji; and Guinea in the longer term.

“For alumina plants, the industry needs higher prices in order to justify the investment,” he said. “For third-party plants, we estimate that $380/mt would cover costs and provide a return. Of course, where companies are building integrated mines and refineries, the situation is different, and the plant cost could be justified at lower prices just to guarantee security of supply.

“Chinese companies are building some refineries overseas, but most of the projects are in China where construction costs are lower. It may be that they have to import bauxite in the future, and one of the results of the Indonesian export ban has been that Chinese bauxite buyers have been diversifying their supply base. Australia, Malaysia and India have been the main winners, and although some Indian companies have had problems with domestic bauxite supplies and have to import their feed, others have not and are able to export—even though the Indian government is taxing exports to discourage this,” Moreno told E&MJ.